I (Cameron) have visited both of these trees. They are both more than 500 years old. They both give me a sense of awe. And they both have taught me a lot about how to grow a firm. There is conformity that comes with size, as if the laws of nature impinge on your existence ever more strongly. In the smallness though there is a freedom to defy that gravity. You can twist and turn into novelty, growing into areas that others would never explore. You become a beautiful alchemical combination of intentionality and serendipity that no one else can hope to reproduce.

For this reason, I love things that are grown (maybe even more than those that are built). And Steel Atlas is growing. We are growing like a bonsai, twisting and turning into new opportunities as a natural extension of where we have been. This essay is our articulation of how.

We will start by sharing an experiment that shows why greatness cannot *just* be planned to gain an intuition for how conviction emerges. We will deepen this understanding through the story of how MongoDB is actually an extension of Dilbert (the comic strip). This will show us why experience matters and you can’t just be a blind person describing the color blue if you want to have real conviction. And finally, we will bring it all together by going out on a couple limbs we are excited about — from radioisotope production / productization to bandwidth constraints and data backhaul.

Going Out On a Limb

In 2015, I had just dropped out of Princeton where I was studying Computer Science to play for a team in Major League Soccer. At the time, I was a devout rationalist. I liked plans. I liked efficiency. I liked the idea that there were heuristics for things, ways to objectively measure progress towards something great.

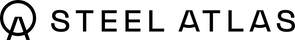

Knowing this, my mom gifted me a new book by two computer scientists focused on artificial intelligence, Kenneth Stanley and Joel Lehman called Why Greatness Cannot Be Planned; The Myth of the Objective. In it, they make the case that in complex domains, objectives may actually be getting in the way of achieving the exceptional. To demonstrate this, they developed a program called Picbreeder where you can “evolve” images. Each initially random image has a “genome”. The program then generates ~15 permutations of that image based on its genome. You pick the most “interesting” one. And the process repeats until you produce an image you are satisfied with.

The above is an evolutionary lineage of a skull image discovered on Picbreeder. So what’s interesting about it? Early images just look like blobs. The middle ones maybe have some abstract patterns. Only right at the end of the evolution does it look anything like a skull. With that, the authors propose a thought experiment. Imagine a government program whose objective is “Evolve a skull image on Picbreeder.”

To execute the government program, scientists dutifully develop a “skull-ness” metric that rates an image from 1 to 10 on how skull-like it is. At each generation, the government program keeps only the images that increase skull-ness and discards the rest. Can you see the problem? All the actual stepping stones to producing the skull score near zero on skull-ness. The key insight is simple. In complex spaces, the stepping stones to remarkable outcomes often look nothing like the outcome itself. Going back to our bonsai, if you only optimize for an end-goal, you prune away the weird intermediate forms you need to grow something great.

It’s been 10 years and I have not stopped being able to see that skull. It haunts the tech industry. My first meeting with it was Kevin Ryan, CEO of AlleyCorp. If you wanted to optimize for co-founding the leading company for a novel database architecture, where should you start? If you guessed Dilbert comics, congrats! You should start working on the skull-ness metric our fake government program needs.

Here are a few more classics: To build the default infrastructure for online video, start by paying women on Craigslist to upload dating videos to your dating site (Youtube). To control the internal chat systems for Silicon Valley, start by failing at building MMO games (Slack). To reinvent online gaming, start with physics education software (Roblox).

But the real takeaway from all these stories is not just that heuristics fail us in complex spaces (like venture capital). It’s that conviction is emergent and, once found, should be followed. After witnessing Dilbert sell out of their merch when they advertised it online, Kevin quit his corporate job, searched for the company (DoubleClick) he thought was going to scale online advertising, and became its CEO. At DoubleClick, Kevin and MongoDB co-founder Dwight Merriman witnessed how Oracle was expensive and failing to deal with the velocity of web-scale work loads. That gave them the conviction to keep doubling down on MongoDB for seven years before the company made meaningful revenue (read more on the story from Sequoia). Now DoubleClick’s ~$3B sale to Google pails in comparison MongoDBs market cap of ~$30B.

So where do we at Steel Atlas get our conviction, especially if you can’t just plan for where it will take you?

Blindness and The Color Blue

Boiled down, conviction is how much more you believe something than others. When correct, it’s how far ahead of the crowd you are. To get conviction though, we often joke that you can’t be a blind person trying to describe the color blue. A blind person can learn all the right things to say about the wavelength of blue light, how it relates to the color red, what emotions it's associated with in culture. But there is a difference between describing and experiencing blue. We believe it’s that seemingly squishy difference between describing and experiencing where real conviction emerges. And it is with that difference in mind that we intentionally structured Steel Atlas.

Kevin’s journey from Dilbert to MongoDB is about actually experiencing the future frustrations of others and having a willingness to step into the seeming unknown based on those experiences. When we thought about starting Steel Atlas, we had a decadal view of the geopolitical shifts and technological tailwinds behind the industrial economy. But this view needed grounding. We believed we needed to see blue, over and over again to be successful, to beat the crowds.

This is why Steel Atlas is structured in such a unique way relative to most early stage funds. We are very concentrated. Our first fund will end up being 10 companies. Our second will be ~12. This means that we only make about one investment per quarter. Importantly though this gives us time. Time that we spend visiting ports and pipe factories, research facilities and reactors. Below is one of the most advanced machine tool shops in the world at CERN.

We travel across the world to do this (United Airlines is the real winner in this game). And we have spent time building high-trust relationships with the people that own and operate these industrial assets because we want to see through their eyes and experience what they experience. This is where our conviction comes from and why we are willing to go out on limbs that others might not.

We went out on a limb in our first fund. We put 25% of it into nuclear companies at a time when it was not clear the US would ever approve a new reactor. One year ago, we even spoke on Bloomberg predicting what would unfold if Trump were elected in terms of nuclear energy. We said we expected de-regulation to drive investment and expedite timelines. As of today, nuclear companies are pushing to turn on reactors per Trump’s executive orders by July 2026. One of them is our portfolio company Valar Atomics, a ~2 year old company that has already demonstrated a thermal version of their reactor and just closed a $130M Series A.

Importantly though, conviction is not static. The crowd is always chasing (or running away). As Ho Nam, the co-founder of Altos Ventures known for his ~$400M investment in Roblox that started out of $86M fund, said in an exchange with Talal on X, “... the key is to continue to build conviction - it's what I call doing due diligence AFTER making the initial investment.” At IPO, Altos owned ~24% of the now ~$70B Roblox.

It's nice to make bets and have them pay off. But if you are too hands off they really are just bets. Investing means not only taking an active role in the outcome but consistently reflecting on what you got right and what you got wrong. What could you have known that you didn’t? What did you think you knew that wasn’t true? This is the work that builds confidence. A high conviction investor without earned confidence is just a gambler.

Concentration allows you to stay close to your companies and do this work. New, growing companies experience the frontier of problems (like data backhaul in remote areas). They try new technologies. Some work. Some don’t. They build things that in the future everyone should be able to buy. They source things from places they would rather not have to (like Russian radioisotopes). They develop new business models in one sector that may apply in others. This is the fertile ground of opportunity. But to see it (to see blue), you need to be close with those that are in it — seeing through their eyes. You need to feel what the industry is growing into. Ultimately, it is this experience that lets us keep on going out on our limbs into fertile territory.

Radios and Radioisotopes

GenLogs → Radios

When we led GenLogs’ seed round in November of 2023, they were making a bold claim. By covering the entire US highway system with sensors to track trucks, they would develop the most advanced supply chain intelligence platform to serve brokers, shippers, carriers, insurers, hedgefunds, state / local law enforcement, the federal government and more. After all, every year, ~4M trucks move more than $10 trillion of goods across the US.

Two years later, GenLogs is closing in on full coverage. It took more than just heroic logistics and sales to get these installed. It was a technical feat as well. Terabytes of data flow off these sensors. Sensors in remote areas with limited bandwidth across. Sensors that are subject to storms and power outages. Every missed truck is potentially lost value. GenLogs had to design their hardware platform in house. The critical component being the radio communication systems that not only determine whether those valuable images arrive on GenLogs servers but that monitor the health of the entire sensor system so they can be reset, patched, or repaired by the GenLogs Sensor Deployment team if needed.

Although GenLogs sensor deployment is large today, it is only growing — expanding into ever more remote areas and countries with more bandwidth constraints necessitating communication systems that potentially utilize a changing array of radio spectrum (satellite, cell, wifi, etc) based on availability. And GenLogs won’t be alone in this. We believe that they are showing the path to massive terrestrial sensor deployments across industrial use cases. More companies will face the same challenges as them.

Unless integrated hardware and software products come out, each new company that follows in GenLogs’ path will face the challenges associated with either 1) building in-house sensor communication systems or 2) adopting off-the-shelf systems that are too complex for non-experts to configure with integration costs that make resilient connectivity difficult. GenLog’s had the expertise to build in-house. Others won’t be so lucky. These companies will miss out on critical data when links drop and could struggle as they develop software to manage data prioritization policies and device health monitoring.

Whether we are looking at companies developing early wildfire warning systems, mining revenue prediction platforms, or drones for the front lines, all of them want robust, integrated, communication systems. Developing the next generation of these could be one of the great horizontal opportunities in industrial technologies.

Transmutex → Radioisotopes

When we invested in Transmutex alongside USV and At One Ventures, it was clear that by developing the first commercially viable, ultra high power cyclotron you could position yourself as a critical player throughout the nuclear supply chain. Using these systems countries could breed domestic fuel supplies to avoid importing enriched uranium from Russia as well as massively minimize their long-term radioactive waste burden from scaled nuclear energy deployment.

But that was not all. Transmutex’s systems can be used to produce the next generation of advanced cancer therapeutics based on unstable radioisotopes. It thus exposed us to the global radioisotope supply chain. Right now, we heavily rely on Russia and China for high value isotopes through Rosatom’s isotope arm (Isotope JSC) and the China Isotope & Radiation Corporation (CIRC). We procure medical nuclides like Lu-177, I-131, and Ac-225 to industrial Co-60 sources for sterilization. Western healthcare, defense, and energy systems are reliant on our adversaries for these scarce materials.

We are living through the risk this creates with rare earth elements today which sit at the center of the US / China trade war. It’s not hard to imagine radioisotopes playing a similar role in the future as isotopes themselves become gating inputs to advanced nuclear medicines, radioisotope thermoelectric generators (RTGs), and next-generation reactor systems. If rare earths were the leverage point for the last cycle of industrial policy, isotopes may be the leverage point for the next one.

If we can secure and scale western isotope supplies, on the other side of that transition is a whole family of radioisotope-enabled products. That looks like nuclear medicines built on beta and alpha emitters — multi-billion-dollar drugs. Large RTGs (think of them like long lasting batteries) placed on the seabed alongside repeaters could bypass the shore-feed power thereby avoiding the thermal limits of today’s undersea data cables and unlocking higher bandwidths between countries without requiring them to lay down new cables. These are just some of the possibilities that an abundant supply of radioisotopes could unlock.

Our Vision

You have to be constantly pruning, training your tree. This is the work of growing a firm, especially as it scales. For there is a certain sameness that comes with size, whether you are looking at big trees or big firms (can you remind me the difference between BlackRock and Blackstone?). A government bureaucracy looks very similar to a corporate one after all. If you want to continue to grow something one of a kind, you always have to be pruning, honing your conviction.

In bonsai, when you prune in one place, it drives more resources to another (potentially a useful lens for things like DOGE). By following, shaping, and supporting specific branches, you can grow something one of a kind. Although I find the big redwoods and sequoias magnificent, we want to be like one of Kunio Kobayishi’s bonsai (all featured throughout this essay). All of Kobayishi’s trees have a real presence. Even though the branches could have been grown in any direction, they seem as if they could not have been any other way. They have conviction about what they are and where they are going. And so do we.