Near-Earth Space: A Deadly Arena, Not an Empty Void

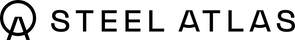

Near-Earth space is a deadly arena of operations, where satellites navigate an invisible battlefield filled with high-speed projectiles. Unlike the controlled environments of terrestrial industries, space is a chaotic domain where lethal debris — often smaller than a bullet — travels at speeds exceeding 10 times the velocity of a rifle round. These fragments, remnants of past collisions, anti-satellite missile tests, and abandoned spacecraft, drift anonymously through orbit, posing an undetectable but catastrophic risk to multi-billion-dollar space assets and constellations. Without warning, a single millimeter-sized fragment can punch through vital satellite systems, causing mission failure, financial loss, and operational disruption on a massive scale.

In one recent example, a publicly traded satellite communications operator tragically suffered a debris collision. The uninsured satellite sprung a propellant leak, shortening its operational life by 15 years. As a result, investor revenue dropped by $678 million across Q2 and Q3 of 2019, while the company incurred $382 million in replacement costs and saw a $200 million sales backlog reduction. The total service restoration cost … $1.26B.

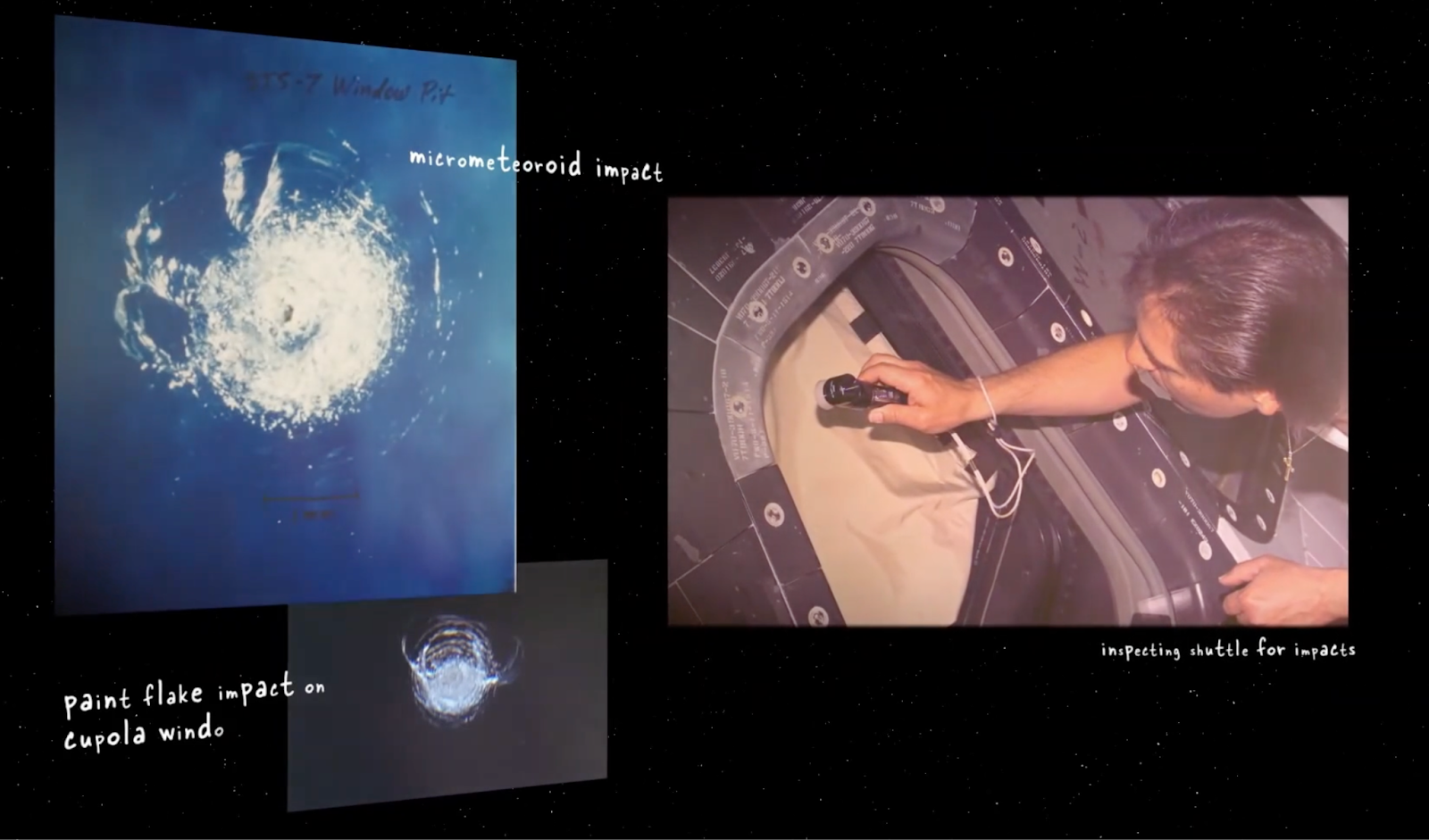

The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) was designed to be humanity’s most powerful space observatory, built to peer into the early universe, study distant exoplanets, and uncover the secrets of cosmic formation. With a staggering $10 billion price tag and a development timeline stretching from 1996 to its launch in December 2021, JWST represents one of the most ambitious scientific projects ever undertaken. Now, just 2.5 years into its mission, the telescope has already sustained visible damage from micrometeoroid impacts. These high-speed debris strikes have degraded some of its mirror segments, forcing scientists to continuously correct its images using advanced algorithms. While JWST remains fully operational, the need for ongoing calibration underscores the ever-present danger of space debris, even for the most advanced scientific instruments ever built.

Echoes at the Frontier: Exploration → Commercialization → Civilization

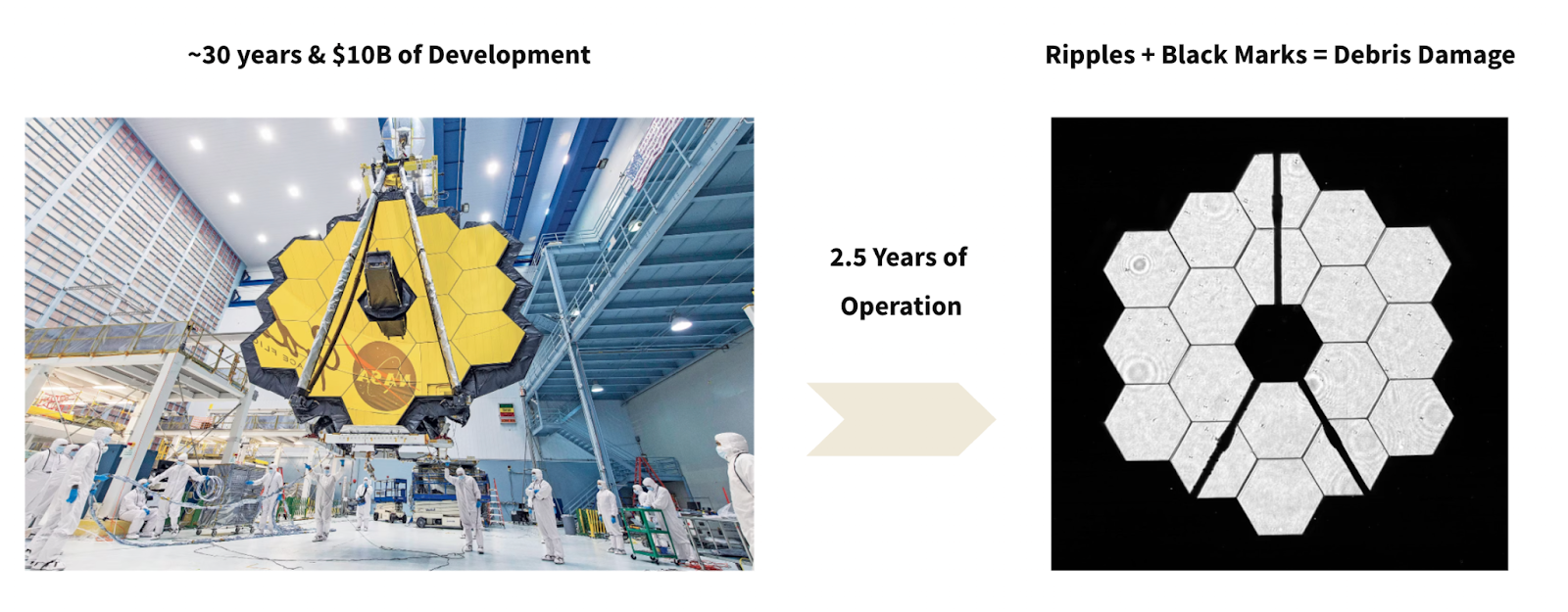

Despite the dangers, the greatest opportunities have always existed at the frontier. The last great frontier was the New World. The next great frontier is space. History may not repeat, but it does rhyme. Although culture and technologies have progressed, the pattern of exploration leading to commercialization leading to new civilization shall once again unfold.

Within the macro patterns are micro patterns, fractally revealing the best opportunities for investment. First, exploration is enabled by new vessels for the safe and efficient transportation of goods and people. Just as maritime vessels including the Caraval / Carrack / Galleon / Fluyt were developed to explore the New World so have new space ships been developed to explore the Moon, Mars and beyond including SpaceX’s Starship / Blue Origin’s New Glenn / Sierra Space’s Dream Chaser Spaceplane. As technological learning curves take hold, lowering transportation costs and risks unlock the inevitable transition from exploration to commercialization.

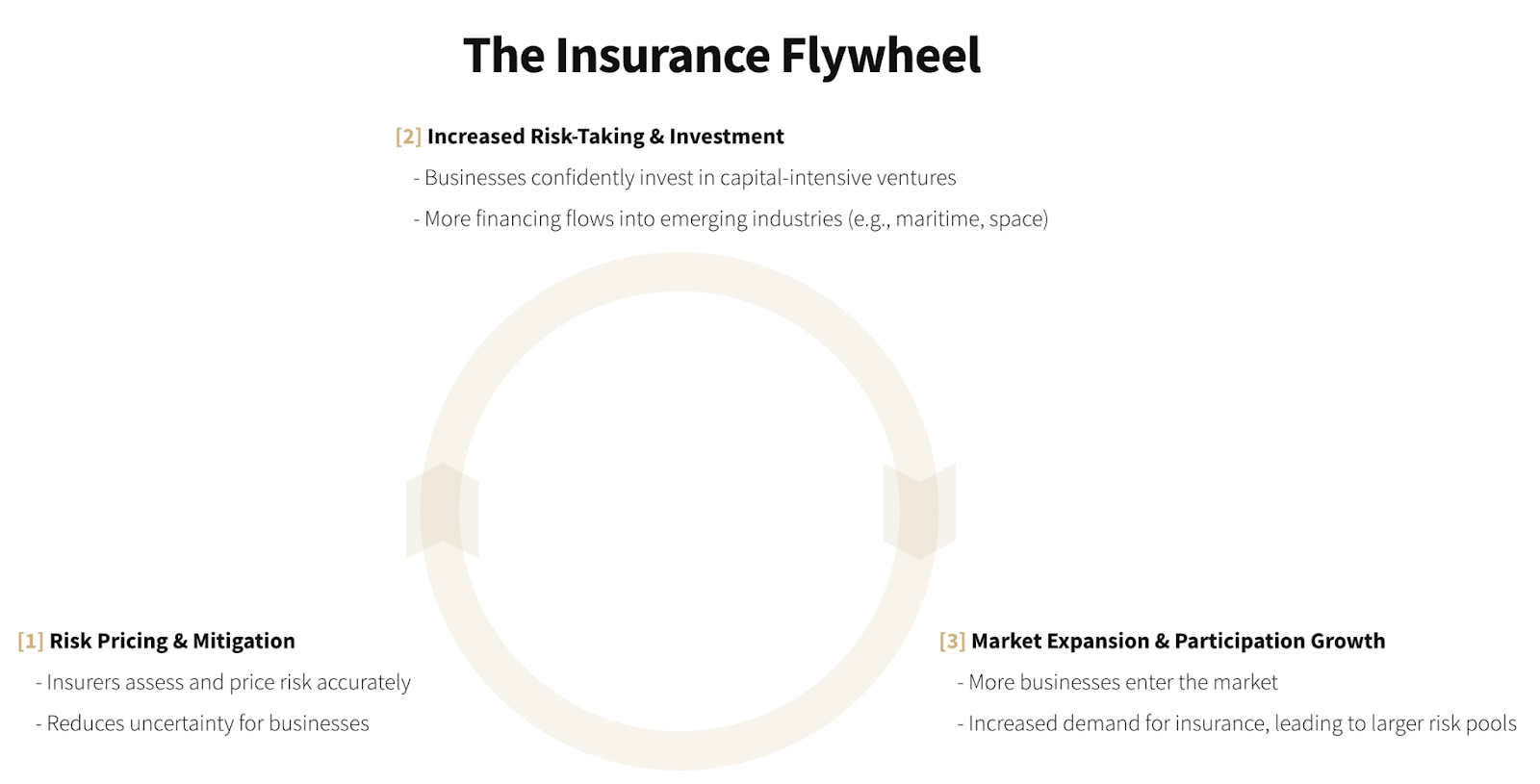

As exploration removes the fog of uncertainty, the perceived economic value of the frontier climbs, kicking the engine of capitalism into first gear. Complementary technologies are developed to increase the reliability of navigating and operating in the new domain. For the sea, we developed the sextant and more precise magnetic compasses. Space brought GPS along with optical and pulsar based navigation. As the empty voids on the map begin to fill with each exploration, the qualitative sense of risk gives way to historical data and quantitative measures. As soon as risk can be measured, so too can it be transferred via investment and insurance. Thus the act of underwriting emerges and the commercialization of the frontier kicks into high gear with large scale capital formation.

Insurance: The Commercial Lubricant

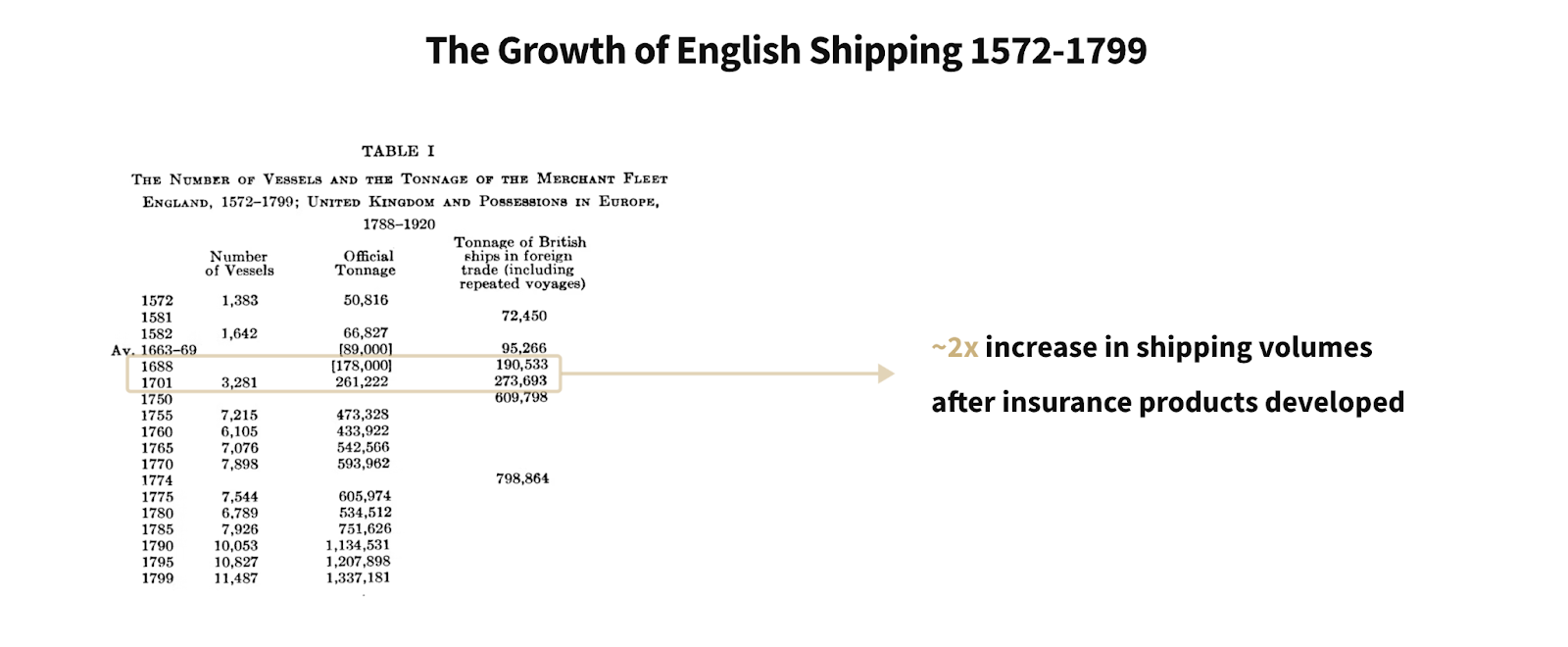

In 1688 the maritime industry shifted into high gear, Edward Lloyd’s Coffee House in London became a hub where shipowners and merchants bought coverage for voyages. Early underwriters at Lloyd’s would sign their names under a ship’s cargo manifest, agreeing to indemnify losses for a premium – giving rise to the term “underwriter.” By the 18th and 19th centuries, Lloyd’s was synonymous with marine insurance, pooling risks across many ships and voyages to make losses manageable. This enabled the growth of global trade by providing financial protection against shipwrecks, piracy, and other perils. As technology improved ship safety and communications (e.g. better navigation, the telegraph), insurers refined pricing based on routes and seasons, and the cost of marine insurance gradually fell as the industry’s confidence grew.

A well-functioning insurance market serves as an economic flywheel by reducing uncertainty, enabling risk-taking, and unlocking capital efficiency. By accurately pricing risk, insurance markets allow businesses to operate with confidence, allocate resources efficiently, and invest in innovation without fear of catastrophic loss. This is particularly evident in emerging industries — such as maritime and now space — where insurance facilitates financing by de-risking capital investments. As risk is better understood and distributed across a broad pool of participants, premiums become more affordable, spurring adoption and market growth. This creates a reinforcing cycle where more participants improve data availability, further refining risk models and reducing costs, which in turn drives even greater participation and industry expansion.

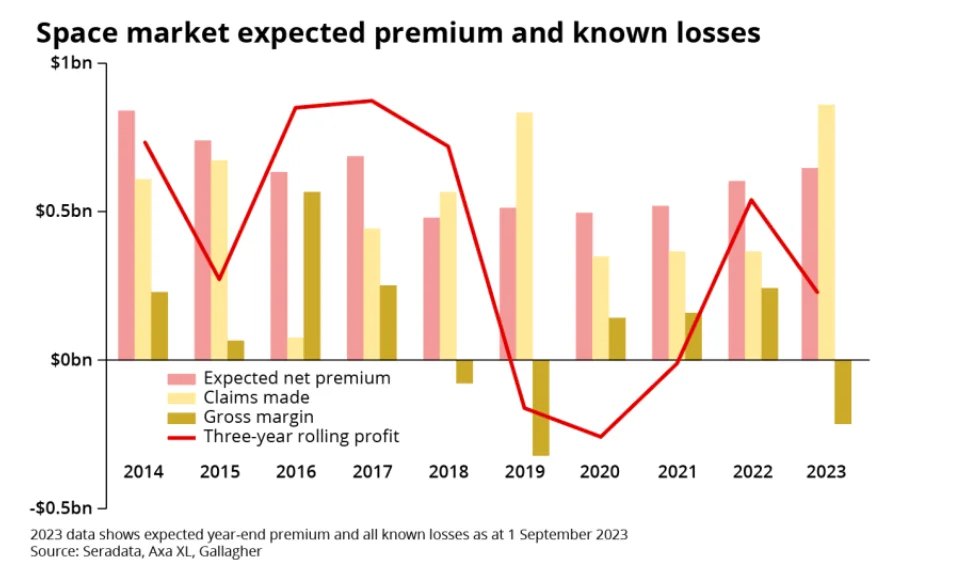

The Broken Satellite Insurance Market

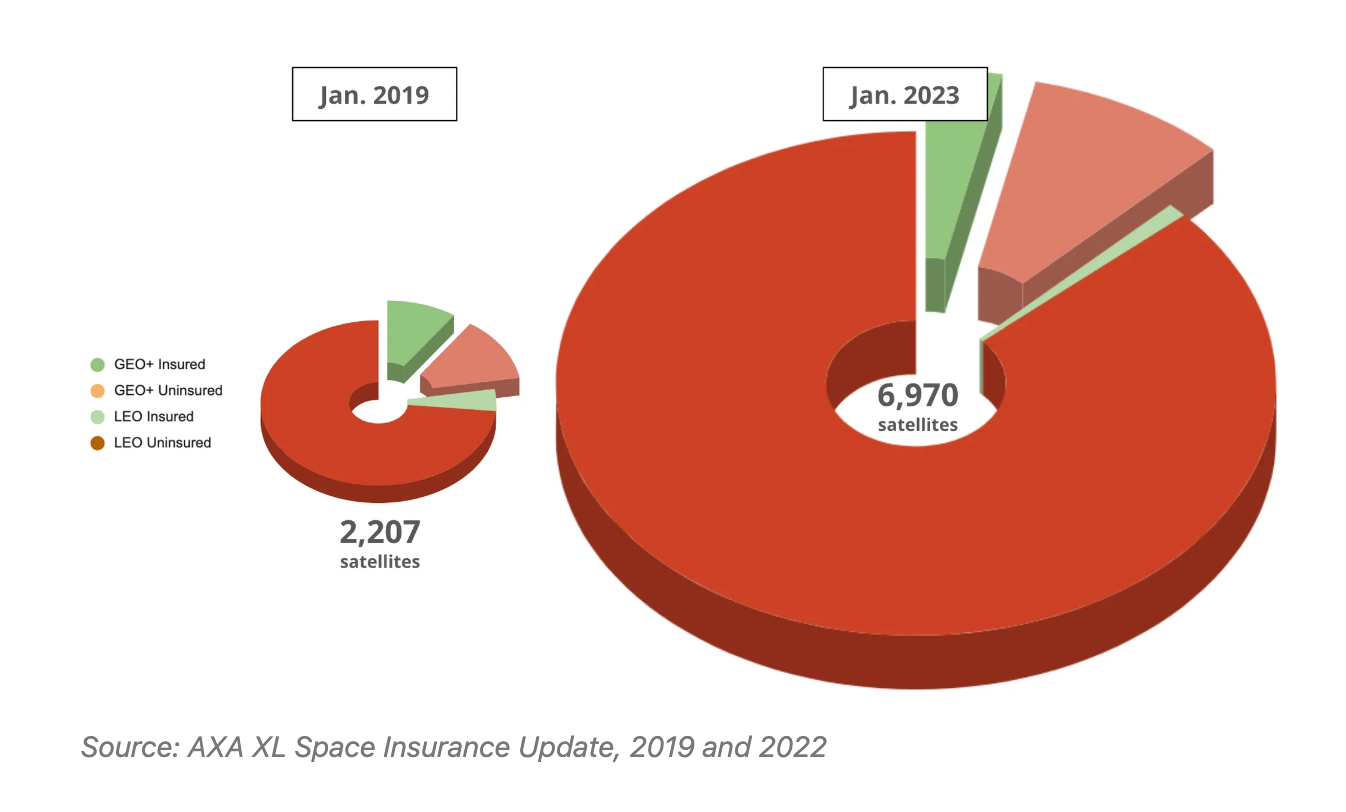

However as of 2025, the satellite insurance market is broken due to a combination of structural inefficiencies, rising risks, and low adoption rates. Historically, space insurance has been dominated by a handful of specialized underwriters and brokers, covering high-value satellites with expensive, all-risk policies. However, as the number of satellites in orbit has grown — particularly in Low Earth Orbit (LEO) with smaller, more affordable satellites — insurers have struggled to adapt. The industry has been hit by a series of costly claims, including the ViaSat-3 malfunction in 2023, which led to a net space insurance industry loss of $438 million.

In response, several major insurers such as AIG, Swiss Re, and Allianz have exited the space market, while remaining insurers have significantly raised premiums and tightened coverage terms. This reaction has further discouraged adoption, creating a feedback loop where fewer satellites are insured, risk is poorly understood, and insurers are unable to price coverage effectively. As a result, premiums have become unaffordable for many operators, particularly in the fast-growing smallsat sector.

ODIN’s Massive Wedge Tracking Tiny Debris

ODIN will unlock the satellite insurance market by providing insurers with real-time, verifiable data on the root causes of satellite failures. Today, only 3-5% of satellites are insured, largely because insurers lack the diagnostic tools to differentiate between failures caused by internal malfunctions and those caused by space debris and other forms of exogenous risk factors. Traditional policies thus bundle all risks together, leading to high premiums that deter adoption, particularly among cost-sensitive smallsat operators.

Solving satellite insurance is conservatively a $10B+ annual revenue opportunity that remains unsolved. By 2030, there could be on the order of 50,000 to 100,000 active satellites at current satellite deployment rates (which could be increased with better insurance products as seen with the maritime industry). Collectively their replacement cost will exceed $300+ billion. With annual premium rates around ~2-5% of asset value, if all satellites were insured for on-orbit risks, just the annual premium pool will be ~$10B per year ($300B * 2% = $6B/year | $300B * 5% = $15B/year).

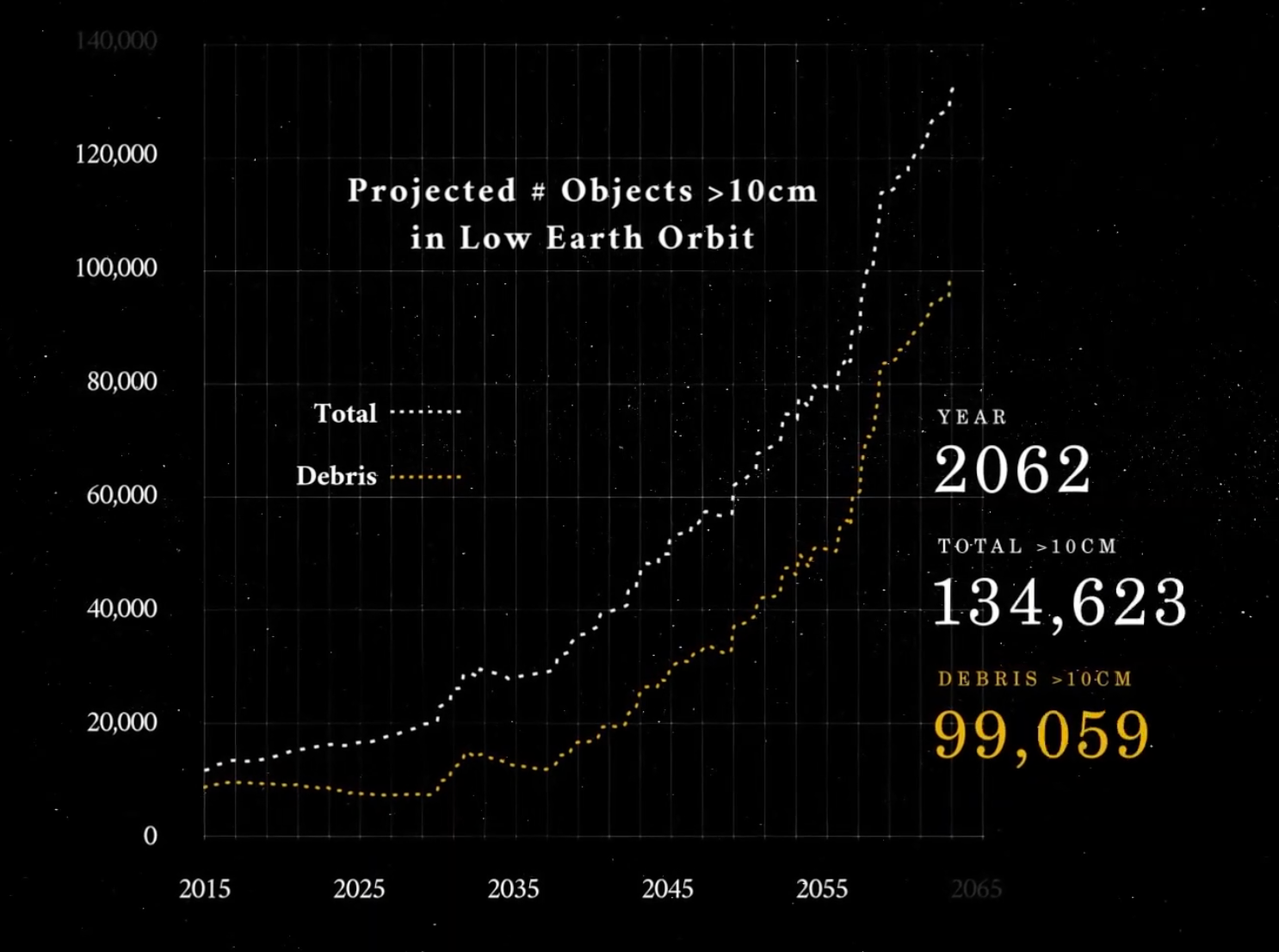

ODIN’s wedge for cultivating and capturing the satellite insurance market is addressing the “lethal, non-trackable space debris” problem. According to NASA, space debris is the single greatest threat to sustained safe operations in Earth orbit, especially in LEO. For perspective, a single one cubic centimeter piece of debris travelling at orbital speeds (20,000, kph) has energy equivalent to a grenade. And yet, we are currently only able to track debris greater than two centimeters in size with methods that are non-exhaustive and intermittent.

Government agencies like NASA and ESA, along with private companies such as LeoLabs, monitor approximately 36,500 objects larger than 10 cm, while an estimated 1 million pieces between 1 cm and 10 cm remain untracked. However, the real threat lies in the vast number of sub-centimeter debris — estimated at over 100 million pieces. These tiny, high-velocity fragments are responsible for many unexplained satellite failures, leaving operators vulnerable to undiagnosed damage and insurers unable to properly assess risk.

ODIN’s Nano Sensors that track plasma / acoustics / light combined with their proprietary signal processing techniques enable satellite operators to get granular, real-time, in-orbit data on debris strikes. This will allow insurers to offer lower-cost, collision-specific coverage for the first time. For smaller satellites (the fastest growing segment), premiums are disproportionately high, sometimes reaching 20-30% of the satellite’s value, making insurance uneconomical for most operators. By allowing insurers to separate collision risk from other failure causes, ODIN enables the introduction of targeted, named-peril insurance products at a fraction of current costs. This will reduce premiums by up to 100x.

The Civilizational Effect of Commercializing Space

The commercialization of space marks the beginning of a new civilizational epoch, one that follows the familiar pattern of exploration → commercialization → civilization. Just as the maritime industry laid the foundations for global trade and the colonization of the New World, space insurance will de-risk the expansion of infrastructure beyond Earth, unlocking massive capital flows into space development.

In the Age of Exploration, the introduction of maritime insurance at Lloyd’s of London in the late 17th century reduced the financial risks of oceanic trade, allowing merchants, explorers, and investors to finance ever-larger ventures with confidence. This kicked global commerce into high gear, leading to the rise of corporate-chartered colonization, the formation of financial centers, and eventually, the establishment of permanent settlements across the world.

Today, space sits at the precipice of a similar transformation. Until now, the space industry has been dominated by government-led exploration and high-risk commercial experiments, but the lack of adequate financial protections has stunted the development of a robust space economy. ODIN is poised to change that by enabling insurance at scale, making space assets a safer and more investable frontier.

As the number of satellites, space stations, and lunar and Martian habitats grows, risk will no longer be an insurmountable barrier but a measured, underwritten factor in capital allocation. This will allow financial markets to extend credit into space, paving the way for specialized investment funds, corporate-backed exploration, and sovereign wealth allocations to space infrastructure — just as maritime insurance once enabled the great trading empires of the past.

In the same way that Lloyd’s enabled the rise of transatlantic commerce, ODIN is unlocking the space economy by transforming orbital risk into something that can be priced, hedged, and insured. Once the financial infrastructure of space is in place, entire industries — resource extraction, in-orbit manufacturing, and deep space logistics — will take root, accelerating the transition from exploration to permanent civilization beyond Earth. The next great cities may not rise along rivers or coastlines, but in low Earth orbit, on the Moon, and on Mars. And just as history remembers Lloyd’s as the bedrock of global maritime expansion, ODIN will be remembered as the insurance backbone of humanity’s ascent into the stars.